Authored By: Jim Plamondon

Series of 3 Articles To Be Published In

CLJ September – November 2021

Introduction

Genetically modified microbes are being fermented in breweries, today, to produce cannabinoids. The combination of genetic engineering and fermentation is called “Precision Fermentation” (PF). The resulting Precision-Fermented Cannabinoids (PFCs) can be sold as isolates, blended with terpenes and flavonoids into pseudo-extracts, and soaked into cheap hempseed flower biomass to make pseudo-marijuana flower. These PFC-based products are likely to satisfy those who want to treat their medical conditions (or get high) inexpensively—that is, everyone except connoisseurs.

Therefore, PFCs will disrupt much of the cannabis farming and processing industry over the next dozen years, give or take. This is an absolute certainty. The only question is: how much of your corner of the industry will be lost to PFCs?

This article is the second in a three-part series that attempts to answer that question:

Disrupting cannabis extracts

Once many PFCs are available, they can be blended with terpenes, flavonoids, and other pure chemicals to compete against the extracts of farmed cannabis (henceforth “farmed extracts”).

To see how, let’s explore an analogy with vanilla.

Imitation vanilla extract

Before 1874, the only source of vanilla flavoring was the vanilla plant. Vanilla extract is made by alcohol extraction of the plant’s mature bean-pods. Farming & extracting vanilla from vanilla plants is so expensive that today, 99% (by weight) of the world’s vanilla flavoring is made some other way.

The chemical that gives vanilla most of its flavor is vanillin, which can be synthesized in many ways. However, the flavour of vanilla bean extract is like a musical chord, with each different chemical contributing a different note. Vanillin is just the loudest note—like THC in cannabis.

In the 1970s, the McCormick spice company made an “Imitation Vanilla” that included the loudest 30-odd notes in vanilla extract’s 200-note chord. McCormick mixed these notes in just the right proportions, and voila! Once baked into a cake or frozen into ice cream, even experts could not tell which cake was flavoured with extract, or which ice cream was flavoured with imitation vanilla. Imitation Vanilla was good enough to be used as a replacement for vanilla extract as an ingredient.

An imitation is good enough for a given purpose when it is subjectively indistinguishable from its model when used for the same purpose by a market segment that can be profitably targeted with the imitation.

Imitation cannabis extract

In this article, I’m using Gelato as the archetype for all medicinal and/or recreational cannabis strains. Why Gelato? Because if a neo-Gelato blend can be good enough to substitute for a Gelato extract’s award-winning flavour, fragrance, and effects, then making good enough imitations of any other strain’s extracts should be easy. (Kudos to Mario Guzman, aka Mr. Sherbinski, for creating such a complex, delicious, and popular strain!)

According to Michael Backes, author of Cannabis Pharmacy: The Practical Guide to Medical Marijuana, “Gelato, like most cannabis cultivars, exhibits significant crop-to-crop variation in terpene content.”

Because of similar variation in vanilla, McCormick modeled its Imitation Vanilla on samples of the world’s highest-priced, best-quality “Bourbon” vanilla extract. One could do the same by modeling a neo-Gelato blend on an award-winning extract of an award-winning harvest of farmed Gelato—the best of the best.

When McCormick created Imitation Vanilla, it was challenging and expensive to identify the loudest notes in vanilla extract’s chord, and their relative proportions. Today, however, identifying the loudest notes in the chord of an extract of farmed Gelato, and their relative proportions, would cost “$50, and would be done in three days, from a 2g sample,” said Mr. Backes.

Mr. Goldman (of Kaycha Labs) agrees. “We would have little difficulty in measuring the top 20-30 components (notes) of a particular cannabis or hemp product.”

Many of cannabis’ notes are still expensive in their isolated form, because cheap PFCs are still several years away. However, we can imagine, today, blending cannabis’ loudest notes together, in just the right proportions, so that the resulting blend is good enough to substitute for an award-winning extract of award-winning farmed Gelato. Let’s call the result of this blending a “neo-Gelato blend.”

How many notes?

How many notes would it take to make a good-enough neo-Gelato blend? For the sake of argument, we’ll use this Gelato vape cartridge made by Jelly Extracts as a model. (I am not claiming that it is “the best of the best.”)

First, we need to know how many notes (that is, pure chemicals) are in the model extract. According to Dr. Markus Roggen, President and CSO of DELIC Labs) and Research Associate at the University of British Columbia, “Jetty Extracts’ Gelato vape cart looks like it is made from distillate and flavours. The distillate will have a few dozen chemicals, mainly cannabinoids. The flavour can have less than 10 to nearly 100 compounds. Therefore, the vape oil probably contains between 20 and 100 chemicals.”

Next, we need to know how many notes would be required to make a good enough neo-Gelato blend. That would require some analytical work, like that done by McCormick for Imitation Vanilla. According to Mr. Backes, “It’s impossible to know how many ‘notes’ would be required to make a credible neo-Gelato blend, until the analytical work was done. My guesstimate: more than 15, but fewer than 50.”

Dr. Bob Melamede, Program Director at the Phoenix Tears Foundation and Co-Founder (and former CEO) of Cannabis Science, agrees. “Medically speaking, there are two basic goals: turn on fat burning with CB2 activity and turn on mental activity with CB1 driving if efficient carbohydrate metabolism. Most of the compounds that will be medically beneficial turn on fat burning and these are found in medicinal plants throughout the world. With just THC, CBD, and CBN, you can address these core functions, using a few dozen other chemicals to adjust for aroma and flavour. Purely medicinal blends would require fewer chemicals than delicious blends.”

The ratio of the number notes in Imitation Vanilla to the number of notes in vanilla extract is approximately (30/200=) 15%. That’s enough to make Imitation Vanilla good enough when used as an ingredient.

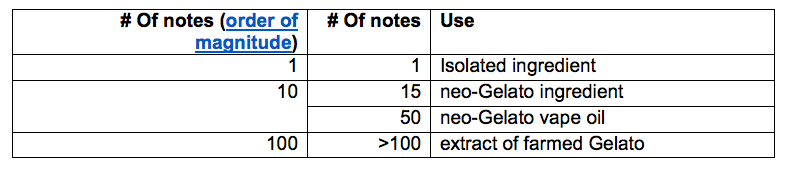

If cannabis extracts have at most 100 notes, as stated by Dr. Roggen, then a neo-Gelato blend need have only 15 notes—at the low end of Mr. Backes’ estimated range of 15-50 notes—to be good enough to be used as an ingredient for edibles, beverages, cosmetics, etc. For direct consumption through vaping, however, more notes would be required—closer to Mr. Backes’ high end of 50. These estimates are summarized in Table 1 (below).

Table 1: An estimate of the number of notes needed for a given purpose.

It is possible to make neo-Gelato blends that are good enough to be used

(a) as ingredients, and (b) as vape oils.

Price

What is the one objective difference between an extract of farmed Gelato and a neo-Gelato blend that every potential buyer could see, no matter what restrictions were placed on cannabis marketing? The price.

Today, a neo-Gelato blend would be more expensive than a Gelato extract because isolated cannabinoids are still expensive. However, over the next several years, as the PFC companies gain scale and experience, PFC prices are likely to fall faster than the prices of farmed isolates or extracts, with the price of the neo-Gelato blends becoming as cheap, then cheaper, then perhaps much cheaper.

You may be thinking: “Price! It’s always price with you, Jim! My customers care about other things more than price!”

Does price matter most?

Imagine that your neighbor walked into his local dispensary and saw two vape cartridges right next to each other:

- Jetty Extracts’ farmed Gelato extract, at $52/g; and

- A neo-Gelato blend that was $25/g.

Which one would your neighbor buy?

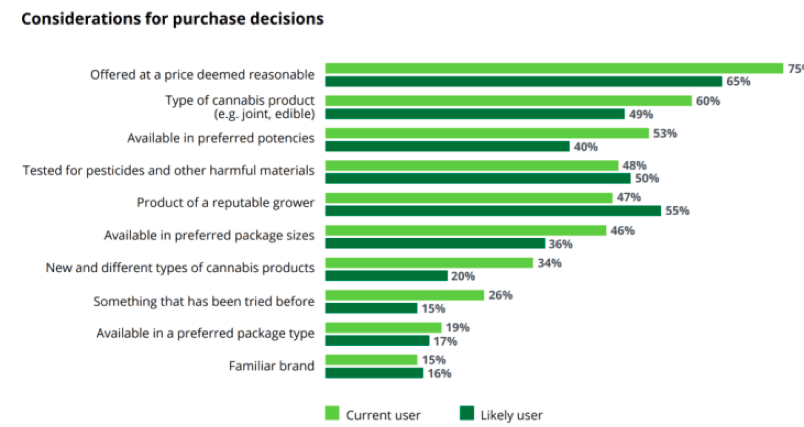

A 2018 study from Deloitte Canada answered that question: 75% of current cannabis consumers would buy the lower-priced cannabis product, all else being equal, with only 15% choosing the familiar brand (see Figure 1, below). Think about that: five times as many respondents bought on price as on brand.

Figure 1: From page 17 of Deloitte Canada’s report, A society in transition, an industry ready to bloom.

Notice that, in Figure 1 (above), price was more important to current consumers (75%) than to prospective consumers (65%). This is common: the more experienced the consumer, the more that price matters. George Zimmer, the American entrepreneur who helped fund California’s Proposition 215—which started the global legalization of medicinal cannabis back in 1996—put it this way in 2019: “I’ve gone from trying to smoke the best pot I can find, to trying to smoke the worst shake I can find, so I can smoke more of it.”

Recently, a 2020 survey of 3,000 Canadians by the Brightfield Group concluded that cannabis consumers decide their purchases by primarily on price.

Yes, price matters, and it matters most—especially to the vast majority of buyers who are not connoisseurs. Let’s call them the deplorables.

80% of cannabis is consumed by 20% of its users (the daily users). Some of these daily users are surely connoisseurs, but most of them could only afford to be deplorables. To paraphrase George Zimmer’s quote (above), most of the daily vapers can be expected to “buy the cheapest vape oils they can find, so they can vape more of it.”

As a ballpark figure, drawing on the sources cited in this section, I assert that the deplorables consume 75% of the cannabis industry’s outputs (by volume), plus or minus 10%—a range of 65%-85%. The connoisseurs consume what’s left: 15%-35%.

The deplorables’ preference for lower prices will tend to shift market share to neo-Gelato blends.

You may be thinking: “So what if the deplorables buy cheap blends? We make quality cannabis extracts. There will always be demand for quality!”

Yes, there will always be demand for quality.

However, these are not the qualities you’re looking for.

What qualities define “quality”?

Disruptive innovations often involve re-defining the metrics of quality. This is not to say that standards are lowered. Instead, standards are shifted to emphasize factors that the previous metrics minimized.

Contamination

The cannabis plant is a hyperaccumulator: it pulls heavy metals and other toxins out of the soil and stores them in the plant itself. Indeed, cannabis was used to decontaminate radioactive soil around the failed Chernobyl nuclear reactor. Even low-grade fertilizer can be a source of contamination.

Making extracts from a hyperaccumulator is just begging for contamination. Therefore, cannabis extracts must be tested to ensure that impurities such as heavy metals, mold, pesticides, excess solvents, etc., are below acceptable levels.

Precision fermentation never touches the soil; it is untouched by fertilizer; and its microbes are not hyperaccumulators. Pure sugar goes in one end, and pure cannabinoids come out the other. On the issue of contamination, PFCs win by a country mile.

Consistency

As noted by Mr. Backes above, cannabis is highly variable. The same strain will produce materially different chemical profiles when grown under different conditions, or under the same conditions by different growers, or with different nutrients, or different light spectra, etc. Even the exact same individual plant will produce a different terpene profile within its upper flowers than within its lower flowers, or within the same flowers next week than this week. Drying, curing, and trimming are additional sources of variation.

However, a blend of pure ingredients can be consistently the same every time. That’s why Coca-Cola tastes the same from every can everywhere in the world. Coke is a blend of pure ingredients, mixed in the same proportions, producing the same experience every time.

If a neo-Gelato blend were modeled on an award-winning extract of award-winning Gelato flowers, then it could deliver an experience that was subjectively indistinguishable from that model every time, everywhere. Such consistency is essential to building a durable and pervasive brand.

On the issue of consistency, PFCs blow farmed cannabis and its extracts out of the water.

Responsiveness

Cannabis connoisseurs seek variety. Breeding a new strain of cannabis could take years, but a new blend could be produced over a weekend. Add a drop of this terpene, and a smidge of a couple more, and you’d have tweaked the neo-Gelato blend.

This is particularly important in the food and cosmetics industries, which introduce new products at a ferocious pace. Companies in these industries could call a PFC blender with a new specification and have a slightly different neo-Gelato blend delivered a few days later. With farmed cannabis, it would be a few years later.

Similarly, producing a new “harvest” of PFCs takes a few days, not a few months as with farmed cannabis.

To the extent that cannabis becomes like fashion, the responsiveness of PFCs could enable a PFC-based company to disrupt the cannabis farming & processing industry the way that Zara disrupted the fashion industry.

On the issue of responsiveness, farmed cannabis and its extracts cannot begin to compete with PFCs.

The ability to produce new blends responsively will accelerate the

shift of market share to neo-Gelato blends.

Sustainability

Indoor-grown cannabis is simply unsustainable, producing between 2,283 to 5,184 kilograms of CO2 per kilogram of cured cannabis bud, depending on the region where it was grown.

Outdoor-grown cannabis uses less electricity, but—depending on where it is grown—its use of water may be similarly unsustainable.

PFCs use less electricity than indoor grows, and less water than outdoor grows, so neo-Gelato blends are more sustainable than farmed Gelato extracts.

THC percentage

An article about the Brightfield Group’s 2020 consumer survey, cited above, quotes Michael Serruya, who operates cannabis retails stores in Canada, as saying “My managers tell me all the time that the number one question we get asked is: ‘What is your highest THC product?’ not ‘What brand is it?’ That’s what moves first.”

In the USA also, the deplorables use “THC %” as their primary measure of quality. The higher the THC, the higher its perceived quality.

Gaming this metric of “quality” would be trivially easy for the PFC blenders.

- If the highest-THC extract of farmed Gelato were 84% THC, then neo-Gelato could be 85% THC.

- If the highest-THC extract of farmed Gelato were 86% THC, then neo-Gelato could be 87% THC.

- No matter how much THC was in the highest-THC extract of farmed Gelato, neo-Gelato could be blended to have 1% more.

Neo-Gelato blends would always win a competition based on THC percentage, all the way up to 100% THC.

The deplorables’ use of THC percentage as their primary metric of

quality will accelerate the shift of market share to neo-Gelato blends.

But…that’s not real quality!

You may be thinking: “Dammit, Jim! Contamination, consistency, responsiveness, sustainability, and THC percentage aren’t the real metrics of cannabis’ quality! Our extracts are truly better! Expert judges will know the difference. Yes, that’s the ticket! Demand for our products will be defended by blind trials!”

And the winner is…

Would blind trials consistently favor farmed Gelato extracts over neo-Gelato? There are not yet any neo-Gelato blends with which to perform this experiment. Therefore, we need to look elsewhere for evidence.

One analogous product is whiskey. It is a good analogy, because the quality of whisky is affected by at least 4,271 unique chemical compounds, which is nearly 10 times more than farmed cannabis (483). Yet Glyph, a whiskey made by blending pure chemicals, has been winning award after award in blind trials by expert judges. This suggests that a good enough neo-Gelato vape oil has an excellent chance of winning blind trials, among expert judges, against farmed Gelato extracts.

Consumers, rather by experts, are likely to prefer a simpler neo-Gelato blend, much as they prefer a simpler wine or a cookie flavored with Imitation Vanilla. Among the deplorables, a lack of “depth and complexity” is likely to enhance sales of neo-Gelato blends.

Blind tests will not slow the shift of market share to neo-Gelato blends.

You may be now thinking: “But…but…but…Aha! Cannabis is a natural product! It’s true that cannabis extracts are made in a chemistry lab using chemical solvents, winterization, particulate filtration, solvent evaporation, crystallization, and then perhaps blending in some terpenes…but that’s natural! Demand for our products will be saved by the public’s demand for natural products! Woo-hoo! Yea, baby!”

Not so fast.

Natural

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) currently defines of the word “natural” as follows (emphasis added):

The term natural flavor or natural flavoring means the essential oil, oleoresin, essence or extractive, protein hydrolysate, distillate, or any product of roasting, heating or enzymolysis, which contains the flavoring constituents derived from a spice, fruit or fruit juice, vegetable or vegetable juice, edible yeast, herb, bark, bud, root, leaf or similar plant material, meat, seafood, poultry, eggs, dairy products, or fermentation products thereof, whose significant function in food is flavoring rather than nutritional.

The European Union’s definition is similar (with subtle differences):

‘Natural flavouring substance’ shall mean a flavouring substance obtained by appropriate physical, enzymatic or microbiological processes from material of vegetable, animal or microbiological origin either in the raw state or after processing for human consumption by one or more of the traditional food preparation processes listed in Annex II [which includes fermentation].

By these definitions, a cannabinoid may legally be described as “natural” if it was extracted from:

- a plant, or from

- yeast fermentation products, including the fermentation products of genetically modified microbes.

You read that right: In the US and the EU, cannabinoids that are extracted from the fermentation products of genetically modified microbes can, legally, be labelled as “natural.” (The UK’s laws are more ambiguous, relying on non-binding guidance.)

In every jurisdiction, these laws are more complex that I have described above, with variations that depend on whether the PFC is:

- Used as a flavor, or a fragrance, or a food ingredient;

- Used in a pharmaceutical, or a cosmetic, or an edible;

- Made in one jurisdiction but sold in another.

The bottom line is that, in many jurisdictions, and for many uses, PFC companies can legally label their neo-Gelato blends as “natural.” (I am not a lawyer, and this is not legal advice. Talk to a lawyer before putting the word “natural” on your neo-Gelato blend’s packaging.)

You may be now thinking: “If we can’t win on ‘natural,’ surely we can win with ‘organic!’ YES! Farmed cannabis extracts will be the only ones allowed to describe themselves as organic!”

Organic

There is nothing “organic” about solvent extraction (and yes, CO2 is a solvent when used in supercritical extraction), winterization, particulate filtration, solvent evaporation, crystallization, and then blending in some terpenes—nor is there anything “organic” about brewing cannabinoids in a vat.

On the other hand, we have the examples of organic wine and organic whiskey. What makes them “organic”? Their inputs. The rule seems to be: “If your inputs are organic, then your outputs are organic, too.” By that rule, PFCs can become organic simply by using organic sugar as their input.

Claiming that farmed Gelato extracts are organic will not slow the

shift of market share to neo-Gelato blends.

Compliance

There’s one last advantage of PFCs to consider: ease of regulatory compliance. Cannabis farms, even if indoors, are large, rambling places, in which many employees touch the plant and have the opportunity divert legally farmed cannabis to the illegal black market. Outdoor cannabis farms have an even greater risk of diversion, requiring extensive security fencing and monitoring in most jurisdictions. Also, as noted previously, cannabis is a hyperaccumulator, requiring extensive testing on each small batch to ensure non-contamination.

It is much easier for PFC companies to comply with the same regulations. A PFC brewery is smaller than an indoor grow-op, let alone an outdoor farm, so it is relatively easy to secure. The brewing process is relatively untouched by human hands—no farming, harvesting, drying, trimming, curing, etc.—so it is relatively easy to secure. It is much more like an industrial chemistry lab, with which regulators are already comfortable. Its batches are large and homogeneous, which reduces the complexity and cost of testing.

Ease of compliance will accelerate the shift of market share to neo-Gelato blends

(especially for medicinal products).

Imitation Gelato: summary

The story so far is that, within the next several years, neo-Gelato blends are likely to be:

- Subjectively indistinguishable from award-winning extracts of award-winning farmed Gelato, initially when used as ingredients and later when used as vape oils;

- Cheaper;

- Less contaminated;

- More consistent;

- More responsive to markets;

- More sustainable;

- Higher in THC;

- As award-winning;

- Labeled as “natural;”

- Labeled as “organic;” and

- More-easily produced in compliance with regulations.

Infused extracts

There’s a middle ground between farmed cannabis extracts and PFC blends: the “infused extract,” which is an extract of farmed cannabis that has been infused with selected PFCs. Consider, for example, a Gelato flower extract infused with a little extra CBD. Or a CBD-rich hemp flower extract infused with PFC-sourced THC and terpenes. There is ample opportunity for cooperation between PFC vendors and vendors of farmed cannabis extracts.

Conclusion

Any company that farms cannabis primarily for isolates and/or extracts, or that processes farmed cannabis primarily for isolates and/or extracts, will be disrupted by PFCs over the next several years. These companies must develop a comprehensive strategy that can delay and/or limit their disruption…or prepare to close their doors. Similarly, cannabis farmers that sell their trim, shake, and/or substandard flower to processors for extraction must expect most of that revenue to vanish over the next several years.

What’s Next

You may be thinking: “OK, maybe we farmers & processors will be out-competed in the isolate and extract markets…but we’ll still have the flower market. Neo-Gelato blends can’t compete with Gelato flower.”

This issue will be addressed in the third and final article in this series, “PFCs: Disrupting Cannabis Flower.”

Jim Plamondon: Precision Fermentation: An existential threat to the cannabis industry – Isolates

Precision fermented cannabinoids: Disrupting cannabis flower